SAN JOSE, CA – With the market for the Internet of Things (IoT) in healthcare expected to be worth 163.24 billion by 2020, medical device manufacturers are increasingly teaming up with digital health developers to make their products IoT compatible. But while the FDA has expressed interest in helping manufacturers develop connected devices, the medical device industry remains heavily regulated, with new policies regarding the design and production of connected devices being released regularly.

Shannon Clark, the CEO of UserWise Consulting, uses her background in medical device development as well as her understanding of current regulations to help device manufacturers design safe and effective products. Brian Zahn, CMN’s Silicon Valley Correspondent, recently interviewed Clark to learn more about how the FDA’s position on human factors engineering will lead to a future of useable devices, reduced complications, and streamlined care.

What is human factors engineering?

Human factors engineering is the application of knowledge about human skills and capabilities to the design of products and services. With respect to healthcare and medical devices specifically, the FDA defines it as the application of knowledge of human skills and capabilities to the design of medical devices, including electrical and mechanical user interfaces, their instructions for use, as well as any labeling on the device and training.

What experience have you had in human factors engineering?

I’ve been involved in the development of medical devices since before 2010. I started at Abbot Laboratories, where I fell in love with human factors engineering. I’ve always loved the idea of designing products – and specifically medical devices – to fulfill user needs in a meaningful way.

I apprenticed with one of the world’s leading experts in human factors engineering while at Abbot Laboratories, and I worked at five different divisions, ranging from Abbot Vascular to Abbot Medical Optics. This experience allowed me to witness a diverse set of human factors engineering programs within a large medical device manufacturer context.

After that, I moved on to Intuitive Surgical and contributed to the design of robot assisted surgical systems. Most notably we launched the da Vinci Xi in 2014. Then, in April of 2015 I founded UserWise in an effort to help medical device developers design safe, effective, and useable medical products.

Taken from Shannon Clark’s presentation Human Factors: What Does This Really Mean for Medical Devices?

What is the current state of human factors engineering in healthcare?

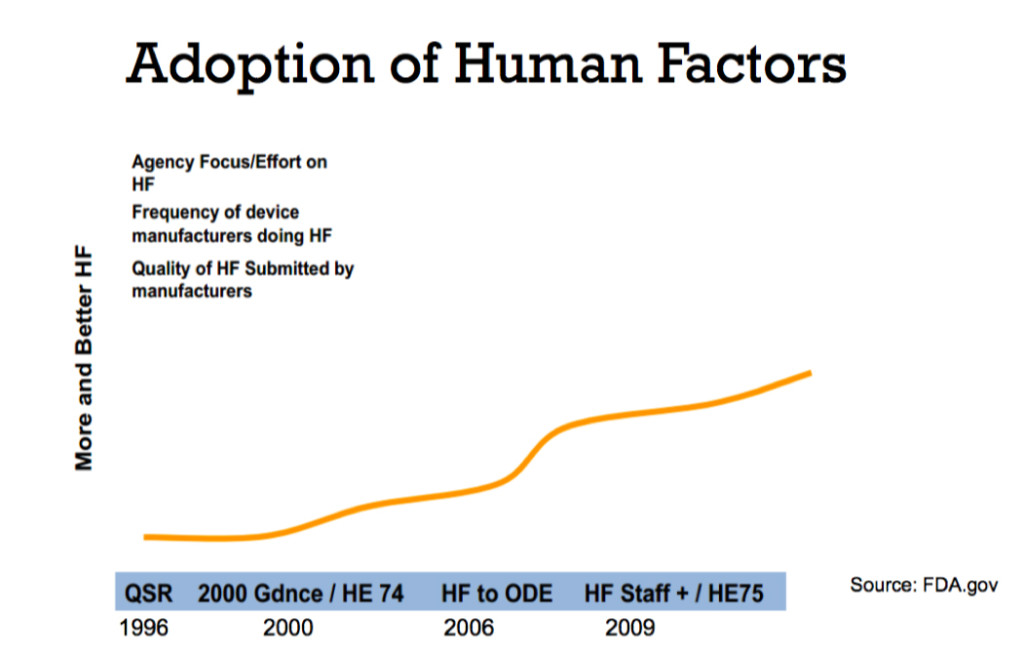

A couple of years ago I would have described human factors engineering as emergent, with early adopters starting to embrace it as part of their development processes. The FDA released a draft guidance for human factors engineering in 2011, and that was a wake up call for all manufactures and designers in the industry – a call for them to stop blaming the user.

Blame is something that’s happened throughout the history of medical devices. A surgeon would make a mistake while using a device, and an easy “way out” for the manufacturer would be to blame the surgeon and say, “It’s his fault, we’re not responsible.” Now the FDA and the industry are embracing the concept of the “use error.” Previously, they used the term “user error” to describe a mistake or oversight, but now they’ve changed the term to “use error,” because use error blames the context of use – and perhaps the device – instead of the user.

On February 3rd, 2016, the FDA released their formal guidance on human factors, which finalized their 2011 draft guidance. It was a very strong stake in the ground, saying that now manufacturers need to take responsibility for any use errors that occur in the field, and that they need to design devices to minimize those use errors.

Can you give an example of a product that exemplifies good human factors engineering in healthcare?

It’s hard to call out a specific product, but there are some manufacturers that really embed human factors design in their products as intended by the FDA. For example, Intuitive Surgical has a very strong usability engineering program. In any software or electro-mechanical interfaces they develop, they ensure that the graphical user interface goes through early stage and final stage simulated use and usability testing to ensure that it’s safe and effective for users, and they also document and assess use-related risks early and often.

Taken from Shannon Clark’s presentation Human Factors: What Does This Really Mean for Medical Devices?

How do you see human factors engineering transforming healthcare?

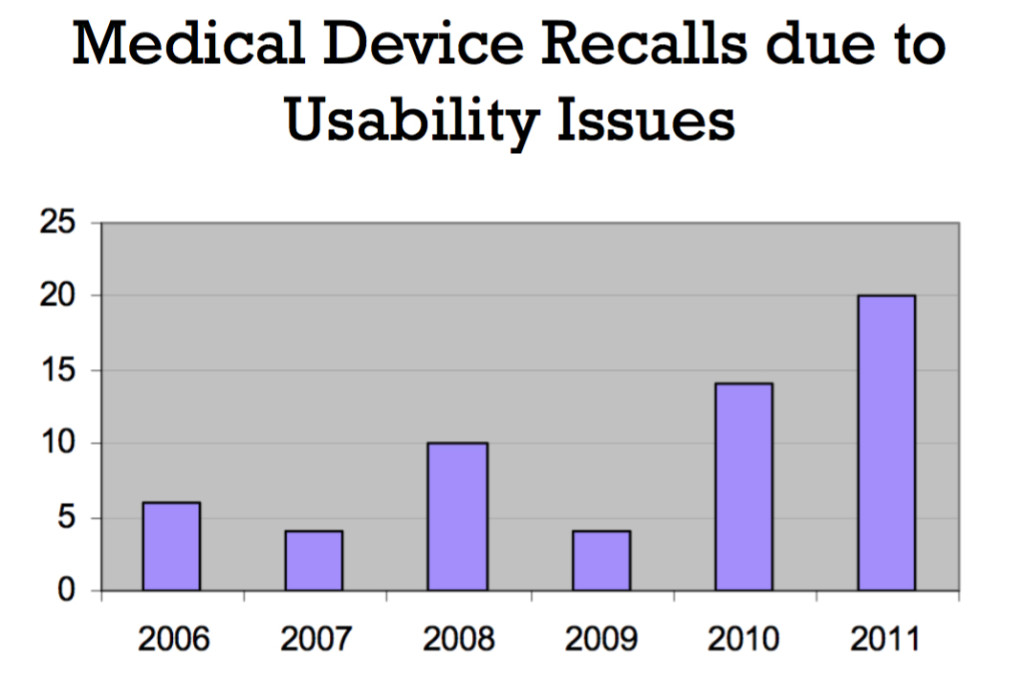

Now that the industry has learned to accept use error as something that manufacturers are responsible for, they no longer blame users for mistakes but instead identify them as an opportunity for improvement. Going forward, I think we’ll really start to see the impact of the 2016 guidance. Typically, it takes between three and seven years to bring a medical device to market. In a couple of years, we’ll start to see hospitals filled with medical devices that are actually useable. We’ll see dropped rates of complications and deaths. We’ll see improved user experiences and streamlined care.

Like the coverage that CyberMed News provides? Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook to make sure you keep up to date on the most recent developments in digital health.

It is great to see the value of applied human factors / usability being embraced by the FDA. In other sectors there has been a focus on identifying “safety-critical” tasks and ensuring that these are properly understood and supported by design and practice. In the medical field, there is a high proportion of such tasks, and therefore a huge scope of application to improve human performance and patient outcomes.